Why vaccines and not antibiotics to fight bacteria?

Lorenzo Bossi

Early Stage Researcher 15, ImmunXperts

September 2020

Vaccines vs Superbugs (highly antibiotic-resistant bacteria that can cause severe human infections). Image ©GAVI, The Vaccine Alliance, www.gavi.org.

The increase in diseases caused by antimicrobial-resistant bacteria, as a result of the overuse and misuse of antibiotics, is one of the main public health concerns worldwide. Treating antibiotic-resistant infections is often very difficult and costly, and people do not always recover (4). If antibiotics are no longer effective due to increasing resistance, even routine medical or surgical procedures such as joint replacements, central catheter insertions, or chemotherapy will be far riskier due to the possibility of untreatable infections.

Recent decades have also witnessed a significant increase in antibiotic use in animals and agriculture. It is estimated that 80% of antibiotic sold in the United States (US) is for animals, to improve yields and meat quality (3). The global use of antibiotics in livestock production and agriculture (estimated at 63 000–240 000 metric tons per year) is expected to increase by 67% from 2010 to 2030 (3), especially in emerging economies. Antibiotics administered to animals are excreted in their faeces, used as fertilizer, or end up in the environment in groundwater. This has an impact on the environment by promoting more resistant microorganisms (1).

An effective way to stop humans and animals from getting infected and thereby preventing the need for antibiotics is to develop a vaccine. Making better use of existing vaccines and developing new vaccines are important ways to tackle antibiotic resistance and reduce preventable illnesses and deaths. According to the World Health Organization, if every child in the world received a vaccine to protect them from infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae (bacteria that can cause pneumonia, meningitis and middle ear infections), an estimated 11 million days of antibiotic use would be prevented each year (4).

Why do vaccines work against antibiotic resistance?

A review published by the Royal Society (2) suggests that there are two fundamental differences between antibiotics and vaccines which could explain why the last drastically reduce the chance of bacteria resistance development.

The first is timing: antibiotics are generally taken once a bacterial infection has already occurred and the bacterial population is large enough to cause disease. At this stage, the bacteria have already multiplied many times. Each time the bacteria divide their DNA is copied, and mistakes in this process can create variation within the population. This means that by the time a patient takes an antibiotic, the bacterial population is already large and varied enough that a resistant strain is likely to have arisen. It has a greater chance of thriving in this environment since other strains, which it would normally have to compete with, are killed off by the antibiotic. This logic is backed up by studies which show that the larger a microbial population is at the time of treatment, the more likely drug resistance is to evolve. By contrast, vaccines are administered prior to infection. Their role is to prime the immune system to fight any future infections, so that they can be brought under control before the bacteria have had a chance to multiply.

A second difference is the intricacy of how vaccines defend against bacterial infection. Antibiotics usually target one specific bacterial protein or mechanism. In some cases, a single mutation is sufficient to change the target so that the drug does not recognize it anymore, providing resistance to the bacterium. By contrast, some vaccines work by exposing the immune system to a high number of bacterial proteins, leading to the development of a wide range of antibodies. These antibodies will in turn form a complex defense mechanism, that prevents bacterial infection and subsequent complications. The chances of the bacteria simultaneously developing resistance to attack from every type of antibody generated following vaccination is rather unlikely (5).

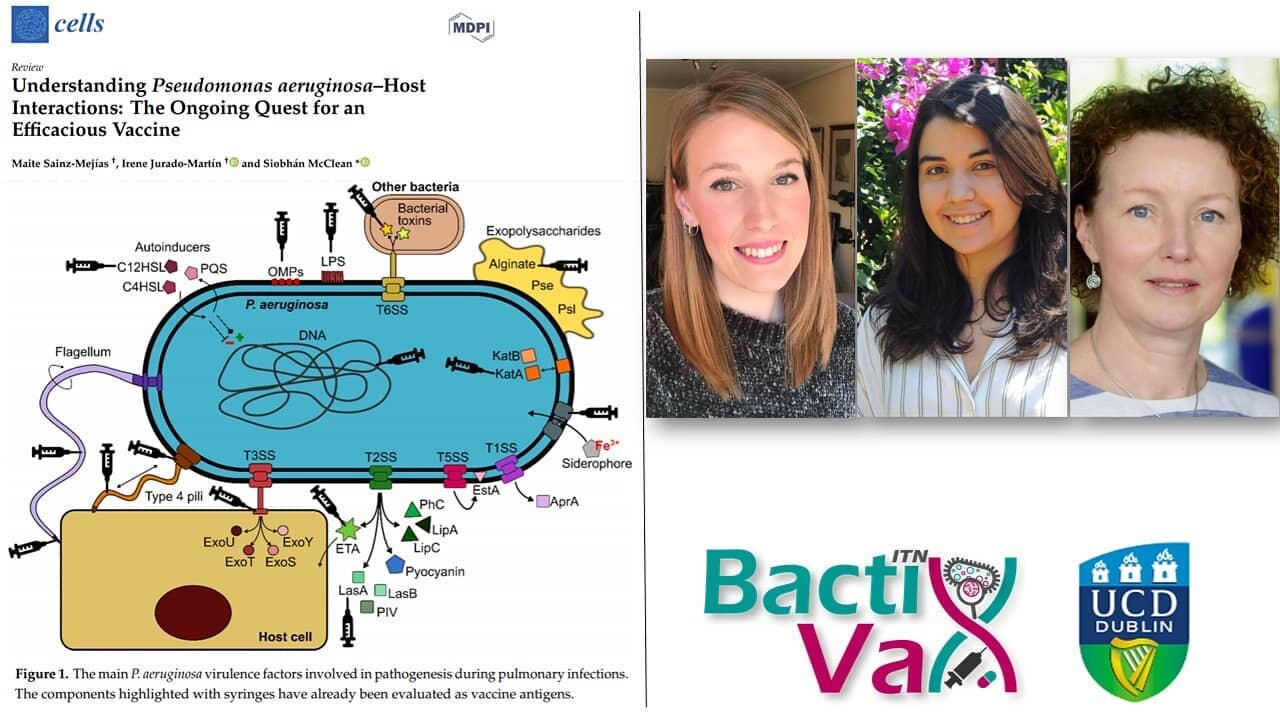

The BactiVax programme focuses on the development of novel vaccines against antibiotic-resistant bacteria to successfully reduce antibiotic use and as a consequence antimicrobial resistance.

REFERENCES

Buchy, P. et al. Impact of vaccines on antimicrobial resistance. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 90, 188–196 (2020).

Kennedy, D. A. & Read, A. F. Why does drug resistance readily evolve but vaccine resistance does not? Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 284, (2017).

Van Boeckel, T. P. et al. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. PNAS. 112 (18), 5649-5654 (2015).

World Health Organisation, https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/why-is-vaccination-important-for-addressing-antibiotic-resistance.

GAVI, The Vaccine Alliance, https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/why-do-vaccines-work-against-antibiotic-resistance.

Recent Tweets from BactiVax

-

RT @mcclean_siobhan: Our fantastic @Bactivax meeting is all over. Great science, great chats and plenty of fun. Thanks to Rita Berisio (… https://t.co/sC7ddNvinE

-

RT @mcclean_siobhan: We had a really informative session this morning on D3 of our @BactiVax summer school: Science Communication & over… https://t.co/sj3zYNHs0h

-

RT @mcclean_siobhan: Amazing talk from Mariagrazia Pizza from @GSK who shared her extensive experience in working on Bacterial #Vaccines… https://t.co/Nm4U46hxJd

-

RT @mcclean_siobhan: Amazing day and it’s been wonderful to see the research projects of each #ESRs develop and grow. 🎉🎉🎉 @REA_research

-

RT @mcclean_siobhan: @LorenzoBossi5 was our last speaker of the day. Based at @immunxperts, he presented his work on the human immune re… https://t.co/THA1OkaxT3